A simple change can give us more doctors and less student debt.

The United States has among the fewest medical doctors per person among rich OECD countries. It is no coincidence that the U.S. is far out of line with international norms regarding physician education, as well. Apart from Canada, the United States is the only wealthy country requiring prospective doctors to earn a separate four-year bachelor’s degree prior to entering medical school. Establishing six-year, single-degree medical education programs for aspiring physicians is therefore about as close to a free lunch for the U.S. health care system as you can get.

Physician shortage in the United States

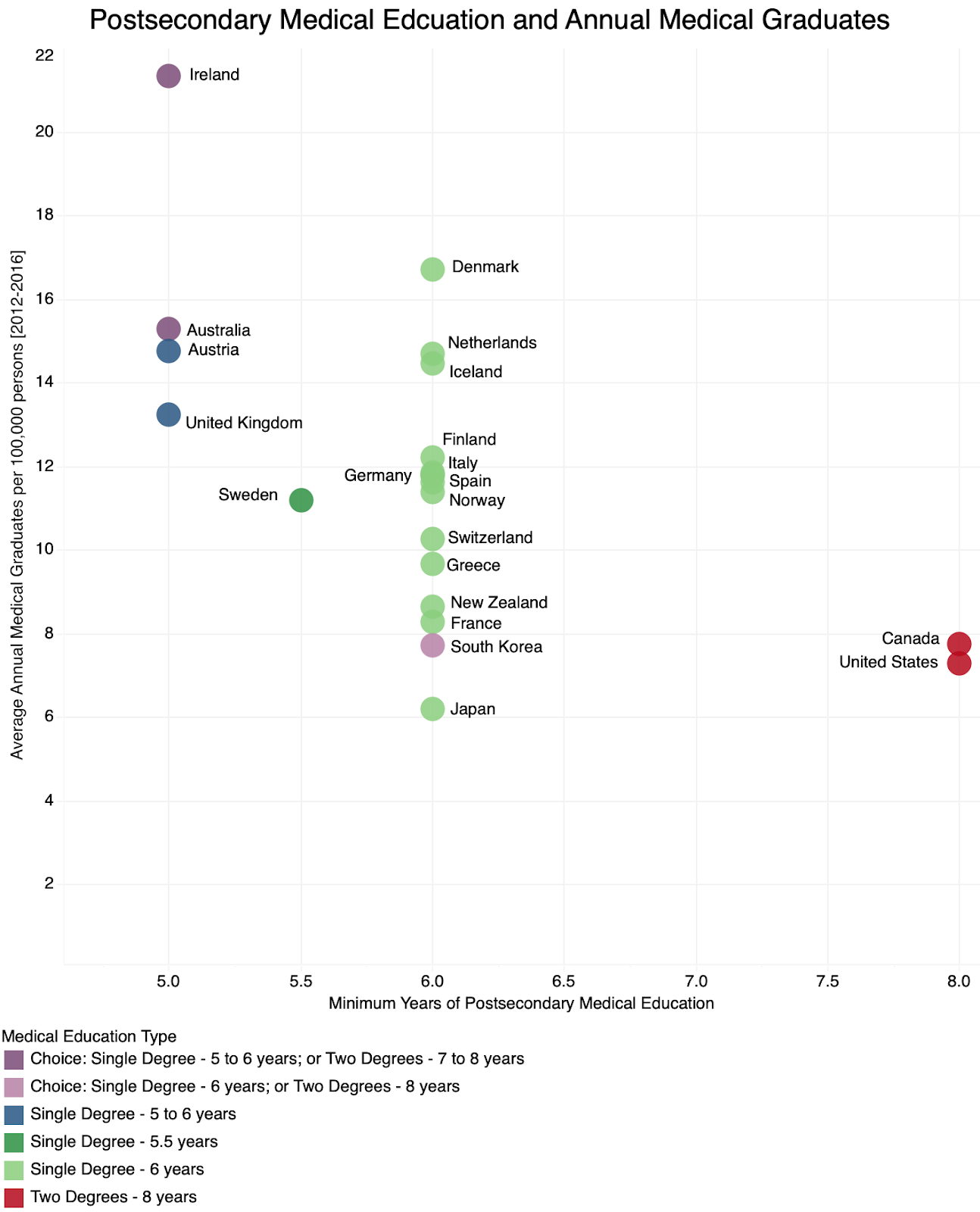

The United States has fewer physicians per person than almost all comparably rich countries, meaning that fewer doctors are available to perform diagnoses and treatments for patients. The United States only beats South Korea and Japan, which are both held back by their near-negligible recruitment of physicians from abroad and lower penetration of women into the profession. The restricted supply of medical providers in the U.S. means that many services are less affordable and less available than they otherwise would be.

Countries get doctors in one of two ways: training them internally or importing doctors trained abroad. The blame for the United States’ relative lack of doctors largely lies with the domestic training pipeline. So while more physician immigrants would no doubt be welcome from the standpoint of U.S. health care, the volume of medical graduates is far behind what is typical internationally.

The impacts of physician shortages are evident throughout the U.S. health care system. Health care costs are higher and access is lower than in comparable countries. According to a survey conducted by the Commonwealth Fund, a third of U.S. respondents reported deferring medical care because of the costs. And this relative lack of physicians is felt particularly acutely in rural areas.

The adverse effects of the physician shortage are also felt by current members of the profession. North American doctors, and particularly those in residency, work more hours than their European counterparts. North American medical residents can be expected to work up to 80-hour weeks and 28-hour shifts. By contrast, European countries largely keep resident duty-hours under 48 per week.

The case for shorter physician training

The U.S. has relatively few physicians per person — despite having the world’s most generous physician compensation. This is because the financial returns to becoming a doctor in America are not actually as attractive as they appear at first glance.

According to the Association of American Medical Colleges, the cost of a four-year medical degree at a public university typically ranges between $150,224 and $247,432; at a private university, the cost typically ranges between $242,660 and $248,920. The cost can even be as high as $398,488. And this is on top of the money already spent on a four-year undergraduate degree, the cost of which, according to the College Board, ranges between $41,760 and $107,280 for public universities and about $147,520, on average, for private universities. The cost can even be over $240,000 in the case of some private universities. Upon entering their first year of residency, American medical school graduates typically have $200,000 of student debt. The debt is $300,000 or more for eighteen percent of medical school graduates, and this does not include all the additional expenses incurred while in universities, such as school supplies or housing.

Given the enormous higher-education costs they take on, it isn’t surprising that 67 percent of doctors opt for more-lucrative specialty care over primary care. Comparable countries devote a far higher share of their medical manpower to making primary care widely accessible. And over the past couple of decades, this trend towards specialty care has only accelerated. Medical students back this up in surveys, with a significant portion viewing medical debt as a deterrent to practicing primary care. If health care is to become more accessible for Americans, the U.S. will need more primary care doctors.

Focusing solely on expanding health insurance coverage is an inadequate response to the physician shortage. Canada, which suffers from a similarly insufficient physician supply, provides an illustrative case here. As a consequence of Canada’s single-payer health insurance system, Canada directs almost half of its limited physician supply into general practitioner roles, an exceptionally high portion, to maximize the accessibility of basic care. While Canada’s strategy of prioritization may amount to making the best of its inadequate physician supply, the result has been exceptionally long wait times for specialty treatments. According to a survey conducted by the Commonwealth Fund, 30 percent of Canadians waited over two months for specialty care, worse than all other countries surveyed. Given the starkly different distribution of physician roles in the U.S., a sudden movement in the direction of Canada’s insurance model runs the high risk of being unworkable without large-scale mandatory retraining of the existing U.S. physician supply. Increasing the supply of physicians, particularly in primary care, is an essential element of making health care more accessible in the U.S., regardless of the coverage scheme.

Countries around the world prove that educating competent medical professionals need not take so long nor cost so much. Medical education in other developed countries is typically structured as a six-year undergraduate education, and even less in countries like Austria and Sweden. Offering a consolidated medical degree not only saves students time and money, but also the hassle of applying to a second program.

The approach to medical education found widely outside of North America makes a lot of sense. The course content involved in obtaining a four-year bachelor’s degree is often largely irrelevant to the practice of medicine. A sizable chunk of U.S. medical students major in the social sciences or humanities prior to pursuing their medical degree. And since medically-relevant majors like biology are not integrated within a comprehensive program of medical education, there is no guarantee that its coursework isn’t duplicative, irrelevant, or inadequate with regard to future success in medical school. There is simply no positive evidence that the attainment of a four-year bachelor’s degree prior to medical school results in higher quality care. Rather, the undergraduate degree’s primary role is as an incredibly expensive signal about an applicant’s preexisting traits. This function can be fulfilled at a far lower cost through a dedicated medical school entry exam for secondary school graduates, combined with a year or two of coursework at the beginning of the medical school program.

Countries such as Ireland and Australia offer potential physicians a choice between two medical education tracks. A two-track medical education system has a lot going for it. One downside of the six-year medical education model is that it locks students onto a long-term trajectory at a relatively young age. Upon graduating from high school, many may lack the certainty necessary to commit to a six-year medical degree, but they may decide during or after a bachelor’s degree that medicine was the right path for them after all. By combining flexibility with cost savings, the two-track medical education system practiced by Australia and Ireland provides a model that the United States ought to emulate.

The chart below shows the average number of annual medical graduates as a ratio of the overall population during the decade between 2012 and 2016 relative to the minimum years of education necessary prior to entering the workforce. While many factors influence the number of medical school graduates, a shorter medical education path entails accelerated receipt of labor market earnings as well as forgone expenses that would have otherwise been incurred during the additional schooling. Among the exceptions that prove this general rule is France, which maintains a restrictive cap on annual medical admissions despite its otherwise supportive medical education policies.

Both health care and education experienced exploding costs over the previous few decades. Some researchers attribute this to low productivity growth in labor-intensive fields, or difficulty transforming the same number of inputs into a greater number of outputs in low-automation sectors. If we want to make health care and education more efficient, it is imperative that we find ways to eliminate clear instances of waste.

The financial burden of medical education assumed by individuals in the United States is higher relative to other countries. Even disregarding countries that offer free or heavily-discounted university tuition, higher education in the United States is much more expensive than in other rich countries. And because U.S. medical schools are organized as graduate programs, aspiring physicians can’t take advantage of directly subsidized student loans for medical school. Allowing for medical students to receive an education on a six-year track would not only cost governments little in terms of direct outlays but may even save a considerable sum through relatively lower health care spending or forgone spending on possible student-debt forgiveness.

States should establish six-year medical education programs

Medical education in the United States can and should be both streamlined and made more affordable, as demonstrated by other developed countries. Demanding that aspiring physicians take on large amounts of debt in order to receive education of dubious relevance amounts to policy malpractice. Policymakers at the state level should facilitate the creation of six-year, consolidated medical degree programs that may be entered upon graduation from high school.

The savings per student are potentially massive. Assuming that a six-year medical degree subtracts one year each from the cost of undergraduate and graduate schooling, it would save aspiring physicians between roughly $50,000 and $100,000. To put these savings in perspective, Elizabeth Warren’s student debt cancelation plan capped per person relief at a maximum of $50,000. As in Australia and Ireland, the graduate track could be retained for those who wish to first pursue a separate bachelor’s degree, but simply not required.

State governments can establish these programs directly by exercising their authority over public university systems. These six-year medical degrees should be structured as a consolidated program conferring both a bachelor’s and a medical degree upon completion.

Given mounting discontent over both student debt and health care access, the federal government has an interest in promoting this policy as well. Congress could provide funds to encourage the establishment of 6-year programs at state universities. And should also ensure that medical degrees are eligible to receive directly subsidized student loans on the same terms as bachelor’s degrees.

On top of making medical school a more attractive investment, this would increase the number of practicing physicians in a mechanical fashion by allowing physicians to begin working as much as two years earlier than they otherwise would be. This would help lessen the burden on currently overworked medical residents and physicians. It also would make it easier for physicians to choose primary care, which is vastly undersupplied in this country.

Undersupply of physicians seriously detracts from the quality of the U.S. health system. While there are other policies that should be pursued as well, including lifting the federal cap on funding for medical residency slots and promoting immigration of physicians from other countries, exempting physicians from having to go deeper into debt to receive unnecessary schooling should be a reform that everyone can get behind.